Abstract

Freedom of speech and expression is the personification of a democratic form of government. Over the years, Section 124A of the Indian Penal Code, that deals with sedition, has been debatable and dubious in the arena of freedom of speech and expression.

The article not only provides entangled or contradicted views of Judiciary and Government, but also deals with the fact of misuse and misinterpretation of the cryptic law due to its archaic nature, including the historical and present time torture against the accused. Moreover, it conveys an urgent need to follow the International guidelines with an ultimate aim to protect and strengthen democracy.

Introduction

The time when Mahatma Gandhi was charged under the infamous and archaic colonial law of Sedition, he famously quoted, “Section 124A, under which I am happily charged, is perhaps the prince among the political sections of the Indian Penal Code designed to suppress the liberty of a citizen…affection cannot be manufactured or regulated by the law.

If one has no affection for a particular person or system, one should be free to give the fullest expression to his disaffection, so long as he does not contemplate, promote or incite to violence.”

India being evolved to the world’s largest democracy from merely a place of British dominance by decriminalizing the inequality norms of Section 377 and 497 under IPC, denotes the predominant nature of fundamental rights provided in the Indian Constitution.

However, Article 124A is one of many problematic laws in Indian Penal Code which still acts as an effective means to restrict free speech and expression under Article 19(1)(a), and has been used by the governments for reasons that are similar to those of our former oppressive rulers.

How History repeats itself:

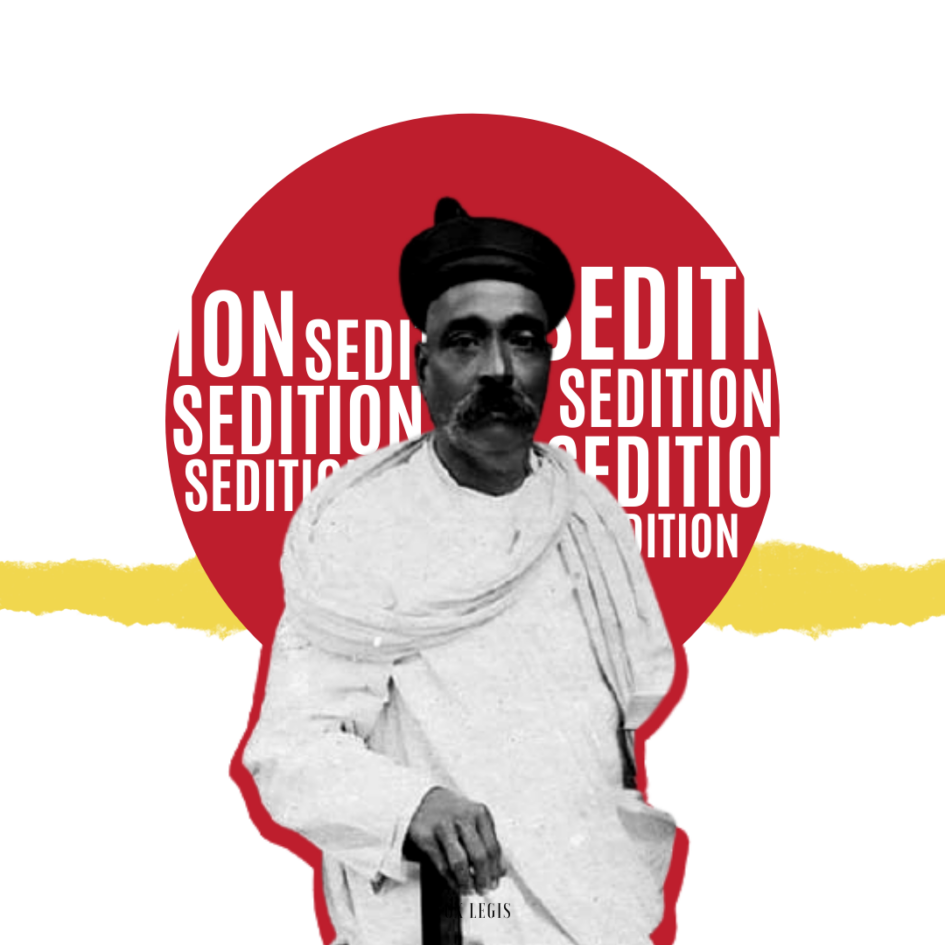

After 1870, when “Sedition” was inserted in the Indian Penal Code (IPC), the first well-known case was of Lokmanya Tilak[1] in 1897, for he wrote articles about mismanagement of the British government in his newspaper “Kesari”. It was held, “the offence consists in exciting or attempting to excite in others certain bad feelings towards the Government.

It is not the exciting or attempting to excite mutiny or rebellion or any sort of actual disturbance great or small. Whether any disturbance or outbreak was caused by these articles is absolutely immaterial”.[2]The privy council continued to support the prosecution and punishment for the offence of sedition as a tool to enhance the power of British rule against Indians and their voices.

But with the emergence of the Constitution, Section 124A became an unreasonable restriction on the freedom of speech and basic human rights. Though it has been criticized by many politicians and leaders over ages, as the law is equivocal in stating ‘nationalistic’ and ‘anti-nationalistic’, over the years every Government chooses to act as a tyrant body in deciding what comes under its jurisdiction.

Words like, “there is no proposal to scrap the provision under IPC dealing with the offence of sedition. There is a need to retain the provision to effectively combat anti-national, secessionist and terrorist elements”,[3] signify how supremely every ruling government wants to shadow their deeds with no questions and arguments from the general public.

The incidents of sedition charges are ascending at a bizarre range and path, with FIRs in the name of sedition been lodged against 49 celebrities for merely writing an open letter to the Prime Minister, raising concerns over the growing incidents of mob lynching,[4] school authorities and parents of student involved in play against CAA with students been interrogated on matter of “sedition”[5], and also against 10,000 tribal people who stood against the violation of their forest land rights.[6]

Recently, Mr. Vinod Dua, a leading journalist was also charged with sedition due to marking deprecatory and critical views on the mishandled COVID-19 outbreak scenario of Government.[7] This confirms how the modern situation is congruent with irrelevant sedition charges against revolutionaries in the past non-independent India.

The irony continues with dissent and uproar in Parliament or abusive outcry by political leaders in public not amounting to “disaffection”, “enmity” or “hatred” whereas the outrage by the general public against implementing exploitative is tagged with the sedition charges.

How the Judiciary and the Government view the law:

The Supreme Court with its judgment in Shreya Singhal vs. Union of India[8], quashed Section 66A of the Information Technology Act to secure citizens’ freedom to express disagreement on social media platforms in a reasonable manner. Justice Nariman in this case stated, “There are three concepts which are fundamental in understanding the reach of this most basic of human right.

The first is discussion, the second is advocacy, and the third is incitement,” believing that discussion is pivotal and without its existence there is no advocacy on what are morals and nationalist ideas of the country. Similarly, in the case of Kedarnath Singh vs. State of Bihar[9], the Supreme Court ruled that any criticism, no matter how strongly worded, is allowed under the ambit of Art 19(1)(a) and in Balwant Singh vs. State of Punjab,[10] the sedition charges on accused were ruled out by the court as mere sloganeering does not amount in instigating and inciting hatred against the government.

With these and many other judgements based on 124A, the apex court considers very few cases where ‘spoken or written’ words would really have the tendency to create disorder or disturbance in public peace, but it fails to recognize the very essence of the law’s existence which is to “seize valid criticism”.

This was truly accepted by the Britishers in 2009, where the judges struck down the law against seditious libel due to its ambiguous and unnecessary nature ‘limiting political debate’ and setting an ‘unworthy exemplar’ for the world.[11]

Analogous to the Judicial point of view in terms of continuation of Section 124A, the Government and the parliament play a problematic role by neither amending nor abrogating the law. This is clearly implied in NCRB data where 93 sedition cases were filed in 2019 with conviction rate at its lowest with just 3% compared to 15.4% in 2018 and 33.3% in 2017.[12]

Thus, there is a serious bone of contention as conviction is not an ultimate goal in cases of sedition charged by governments, rather it’s just a symbolic step to differentiate someone as disobedient towards the country.

There are many other problematic issues surrounding the exhaustive and uncertain definition of sedition, like, a police constable is the first authoritative person to decide whether a speech or cartoon will cause disaffection or contempt towards the government which is more problematic due to non-implementation of police reforms in our nation, leading to a legally wrong arrest.

There isn’t any provision to penalize the Centre and the States with no compensation paid to the victims in case of wrong application of the sedition law. Moreover, criticism in a vilified or dishonest way against senior authorities can amount to “criminal defamation” u/s 399 and 500 of IPC, but it does not create a ground for sedition.

These attributes are blatantly ignored by the Government unlike the 42nd Report of Law Commission India, that termed it as “defective” and “archaic”.[13]

What is the Standard International view?

International law provides immense significance to free speech and expression and guarantees the enforcement of the basic human rights by various treaties and conventions with individual member countries. Most importantly, The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), which was already ratified by India in 1979, prohibits restrictions on ‘freedom of expression’ on ‘national security grounds’ unless they are provided by legitimate rules considering serious threats clearly stating, “The Constitution of India and international law recognize the right to freedom of expression, and this right extends to speech that offends or disturbs.

Authorities must respect this fundamental right, not seek to curb it.”[14] Also, in order to safeguard national security or maintain public order some ‘specific justification’ is needed in compliance with Article 19 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR).[15]

The universal democratic importance has been highlighted in numerous cases, for instance, the African Commission on Human and People’s Rights has held, “Freedom of expression is a basic human right, vital to an individual’s personal development, his political consciousness, and participation in the conduct of public affairs in his country.”[16]

Moreover, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights provides that “In the exercise of his rights and freedoms, everyone shall be subject only to such limitations as are determined by law solely for the purpose of securing due recognition and respect for the rights and freedoms of others and of meeting the just requirements of morality, public order and the general welfare in a democratic society.[17]

With all these recognized international norms to protect society’s freedom of speech, India as a developing democratic country needs to implement their guidelines and eradicate the archaic law of sedition due to its conflicting nature against international human rights.

Conclusion

Questions are bound to persist. Questions like, “are state-manufactured and politicized standards enough to call one protester as anti-national?”, “Under the right to dissent and criticize, can a citizen not express dissatisfaction with the policies and steps of the government which are directing the life of every individual of the country?” If the law is unable to answer, no authority would be able to coherently answer these questions.

Undoubtedly, there is no need to revisit this law due to its negative crux and originality towards India’s democracy. With global radical and liberal democracy, it is irrelevant to keep this law which not only strangulated the voices of our freedom fighters in the past as a British tool of oppression but it continues to do the same in present and probably will continue to drag this despotic cycle in future.

There is also an urgent need to understand that there are many sedition cases which are beyond the high profile-urban ones and are ignored due to lack of “terrorism factor” and “effective” media coverage, ultimately throttling dissent and democracy.

In light of the above observations, it is high time for the Indian legislature and judiciary to reconsider the existence of sedition provisions, especially, Section 124A as there are various other statutes that govern the maintenance of public order with less obsolete and stringent punishments.

By Shubhangi Ghelot, 3rd Year B.A. LL.B. (Hons.), Faculty of Law, The Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda, Vadodara

9 April 2021 at 2:19 pm

This is the perfect blog for anybody who hopes to find out about this topic.

You definitely put a brand new pin on a topic which has been discussed for decades.Wonderful

stuff, just excellent!

12 September 2021 at 3:47 pm

Hey! Would you mind if I share your blog with my facebook group? There’s a lot of people that I think would really enjoy your content. Please let me know. Thanks

13 September 2021 at 6:40 am

Sure, thanks!

21 December 2021 at 3:08 am

I appreciate, cause I found just what I was looking for. You have ended my four day long hunt! God Bless you man. Have a nice day. Bye