“It is certain, in any case, that ignorance, allied with power, is the most ferocious enemy justice can have.” – James Baldwin

Abstract

In India, the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act, of 1967 (UAPA) is considered major legislation in keeping terrorism under control. However, the Act has been criticised in many instances for its stringent and stern provisions. Where the objective of the Act was actually to free India from the shadows of terrorism, the provisions in reality tie down India to the arbitrary and oppressive acts of the executive.

This article deals with analyzing the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act, of 1967 and how the judiciary plays an important role in securing the country against the evils of the Act.

Introduction

Terrorism is an unlawful destructive method of political action that uses violence and coercion to cause fear in order to meet the desired political ends. Such ends are achieved by killing or injuring innocents. These acts are usually planned by organizations of political nature including either leftist or rightist objectives, religious organizations, or nationalist groups.

The United Nations General Assembly describes Terrorism[1] as “Criminal acts intended to provoke a state of terror in general public…for political purposes… (which) are in any circumstances considered unjustifiable, whatever the considerations of a political, philosophical, ideological, racial, ethnic, religious or any other nature may be invoked to justify them”.

In India, the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act, of 1967 defines terrorism as acts that intend to threaten the unity, integrity, security, or sovereignty of India or strike terror in the people of India or a foreign country [2].

In India, terrorism has mushroomed in the past twenty years including the Pulwama Attack (2019), the Uri Attack (2016), the Mumbai Attack of 26/11(2008), the Delhi Bomb blasts (2005), and others. After the Mumbai Attacks of 26/11 in 2008, stern laws relating to terrorism have been implemented in the country.

Laws in Application

India, currently, has two major legislations regarding anti-terrorism, namely, the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act, 1967 to which major amendments were made in 1969, 2004, 2008, and 2019 and the National Securities Act, 1980.

The Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act 1967 (“UAPA”), deals with the definition of terrorist acts and related terms each followed by punishments. As per the Act, Central Government has the power to declare any association to be unlawful subject to confirmation with the Tribunal set up under the said Act presided by the Judges of the High Court.

The Act also enlists punishments and penalties for persons continuing association in any form where such association is declared to be unlawful. Further, the Schedules annexed to the Act list down identities of organizations declared unlawful as well as terrorist organizations.

The National Securities Act, of 1980 is a legislation that is related to preventive detention. The object behind the enactment of such a law was to prevent acts of individuals which are adverse to the interest of the State or a threat to the security of the State.

The Central Government and the State Governments, in relation to their respective states, were given the power to detain any individual (Indian or foreign) if their actions are in any manner prejudicial to the country.

Examining the definition of “Terrorism” in accordance with UAPA

The UAPA is sometimes considered severe and stringent. Certain controversial provisions of the Act lead to its misuse and cause unnecessary discomfort to individuals. This Act has led to the harassment of many innocent individuals because of its provisions which may seem anti-humanist and contrary to fundamental rights at times.

The definition presented in the concerned Act, itself is considered disputed in nature. According to the recommendations prescribed under the United Nations Report of the Special Rapporteur on the Promotion and Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms while Countering Terrorism, the member states must ensure that the “Definitions of terrorism…..in national laws must not be overly broad and vague….must be precise and sufficiently narrow….”[3].

However, there exist inconsistencies between the recommendations by the United Nations and the definition provided by the UAPA. First and foremost, no particular and express definition of the term ‘terrorism’ is mentioned in the provisions of the said Act.

It merely provides the definition of a ‘terrorist act’ as an ‘act with intent to threaten or likely to threaten the unity, integrity, security, economic security or sovereignty of India or with intent to strike terror or likely to strike terror in the people or any section of the people in India or any foreign country’ [4].

A bench consisting of Justice Siddharth Mridul and Justice Anup Jairam Bhanbhani at the Delhi High Court in June 2021 mentioned that the definition of ‘terrorism’ or ‘terror’ is not at all provided in the UAPA [5]. At best, the definition of ‘terrorist act’ is proffered by the Act, which deals broadly and predominantly with the death of, or injuries to persons, damages to property, criminal force, kidnapping, abductions, etc [6].

Nowhere is it considered to match the standards prescribed by the United Nations. Such a definition is considered by many jurists as vague and easy to exploit. Former Patna High Court Judge, Anjana Prakash in June 2021, criticized the definition by saying “…definition of ‘terrorist act’ in section 15 of UAPA is so vague that it is susceptible to misuse….” [7]

Analyzing the provisions of UAPA with reference to Arrest, Detention and Bail

The Act which now deals with terrorism, money laundering for the purpose of terrorism, and to pronounce organizations and individuals as terrorists was initially not a terrorism law. Originally, it dealt substantially with activities against the sovereignty and integrity of the country. ‘Terrorism’ was added to the Act after the 2004 amendment and thereafter in 2008 and 2009 certain stern anti-terrorist provisions were inserted after the 26/11 attacks in Mumbai.

However, in the recent years, the contentious Act has been exploited, misused, and misemployed on many occasions. It is because of the excessive and arbitrary powers given by the Act to the executive that the Act remains in constant feud and friction.

Moreover, there were amendments made in the year 2019 as per the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Amendment Act, 2019 [8], which further adds to the complexity of the situation. The said amendment has brought alterations in section 35 [9]. Prior to the amendment, only organizations linked in any way to terrorism could be notified, by the central government, as ‘terrorists’ under Schedule I of the Act.

After the amendment, a new schedule namely, Schedule IV was introduced into the Act and section 35 was altered. The amendment conferred upon the central government, the power to declare any individual as a ‘terrorist’ as per the provisions of the Act and notify the same under the newly added aforementioned schedule, that is Schedule IV [10].

The Act authorizes the central government to appoint executive officers as ‘Designated Authority’. The Act through its section 31 [11] empowers such Designated Authorities to have all the powers that are given to the civil courts with respect to an inquiry of matters related to the Act.

The doctrine of separation of powers, in my opinion, has been grossly violated and an arbitrary excess in the powers of the executive can be seen. The 2008 Amendment of the Act inserted the provisions of Section 43A to 43F which are, in my opinion, a matter of huge controversy.

The Amendment confers upon the aforementioned Designated Authority wide powers of arrest and search on the mere basis of suspicion. Such suspicion can be acquired even on the most obscure grounds as per the provisions of the Act [12].

It is also worth mentioning that all acts declared as offences under the UAPA are cognizable in nature irrespective of what is mentioned in the Code of Criminal Procedure [13]. This along with wide powers of arrest has led to several arrests but no actual convictions, causing a redundant deprivation of their right to Liberty and leading to unnecessary inconvenience to the individual arrested.

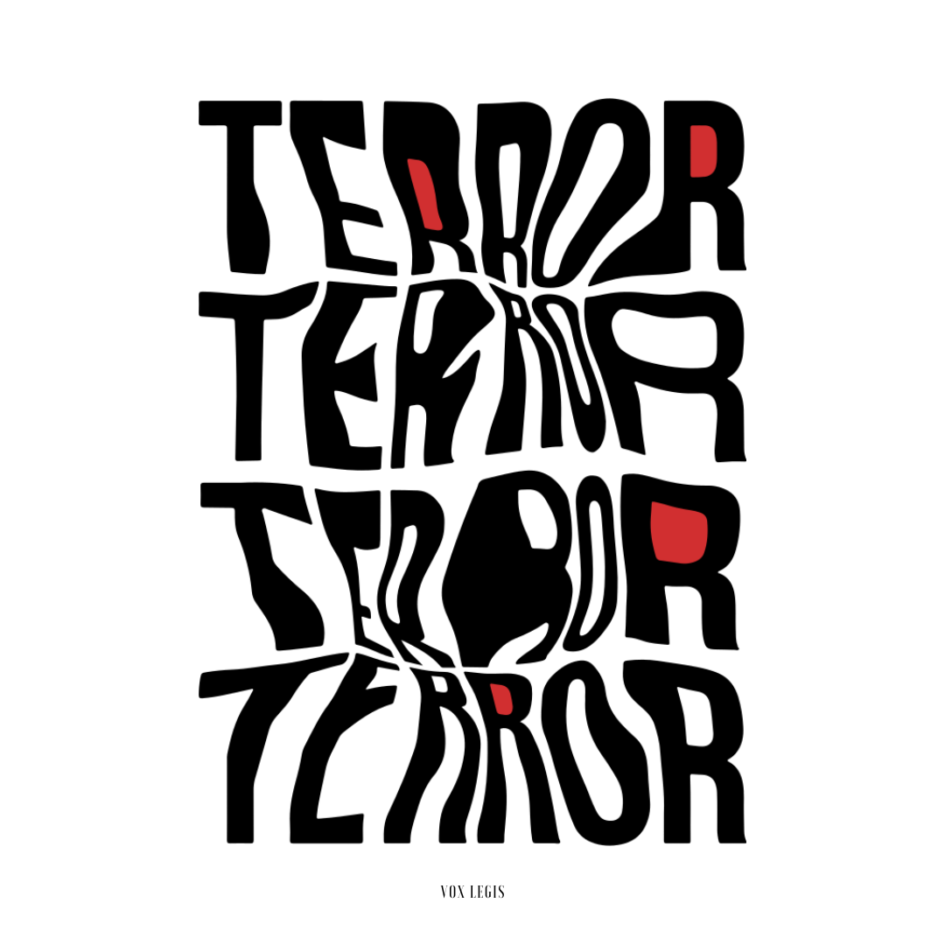

In response to questions put forward by the Rajya Sabha, the Ministry of Home Affairs submitted the following data on 24th March 2021[14]:

According to the reply by the Ministry of Home Affairs to the questions of Rajya Sabha answered on 1st December 2021, 1321 people were arrested under UAPA in 2020 out of which only 80 people were convicted by the courts [15].

The aforementioned data hereby gives a clear conclusion that while a substantial number of arrests occur in the country on the mere basis of suspicion; the actual convictions awarded by the courts are infinitesimal compared to the arrests. Arrests are being conducted in a baseless manner with no actual evidence in hand.

Such false arrests made by the authorities tend to harass innocent individuals and affect the person in all aspects of life. A report on the ‘psychological impact of being wrongfully accused of criminal offences’ identifies consequences such as loss of identity, stigma, psychological and physical health, negative attitude towards the justice system, impact on finances and employment, and other traumatic experiences as major effects [16]. Such experiences affect individuals even after the acquittal.

A group of aeronautical engineers belonging to Kashmir working in Delhi was arrested by the Delhi Police Special Cell in 2006 and were accused of being associated with Lashkar-e-Taiba (notified as an illegal organization and banned). They were under custody for 5 long years and later acquitted [17].

Furthermore, the UAPA allows the presumption of guilt in cases where arms and fingerprints are recovered from the possession of the accused [18]. The aforesaid provision draws the burden of proof on the accused to prove himself innocent. This is against the due process of law and contrasts the legal principle of “presumed innocent unless proven guilty”.

This provision can be easily misused by the police authorities by presenting made-up and false recoveries from the accused.

The Delhi High Court granted bail to 3 student activists who were arrested by the police for being associated with Delhi Riots (2000). The Court held that the Police tried to build a false case base and failed to show any prima facie evidence which would prove such accusations were true [19].

Apart from groundless arrests, another major issue is in relation to the framing of the Chargesheet. The authorities tend to arrest persons on the basis of mere suspicion and later on find it difficult to search for any sound evidence against the so-called accused. This causes delays in framing Chargesheets.

Section 43C provides override of the provisions of the Criminal Procedure Code which are inconsistent with the UAPA. Further, according to the Criminal Procedure Code, an accused should be detained in custody for not more than 60 days while the Chargesheet framing is still pending and such period may be extendable to 90 days in certain cases.

However, under the UAPA, the pre-chargesheet framing detention is for a period of 90 days. Furthermore, the 90 days pre-charge detention period can further be extended to a 180-day pre-charge detention period if no sufficient evidence is found against the accused [20]. This way the Act itself restricts the liberty of an accused by contradicting the provisions of CrPC.

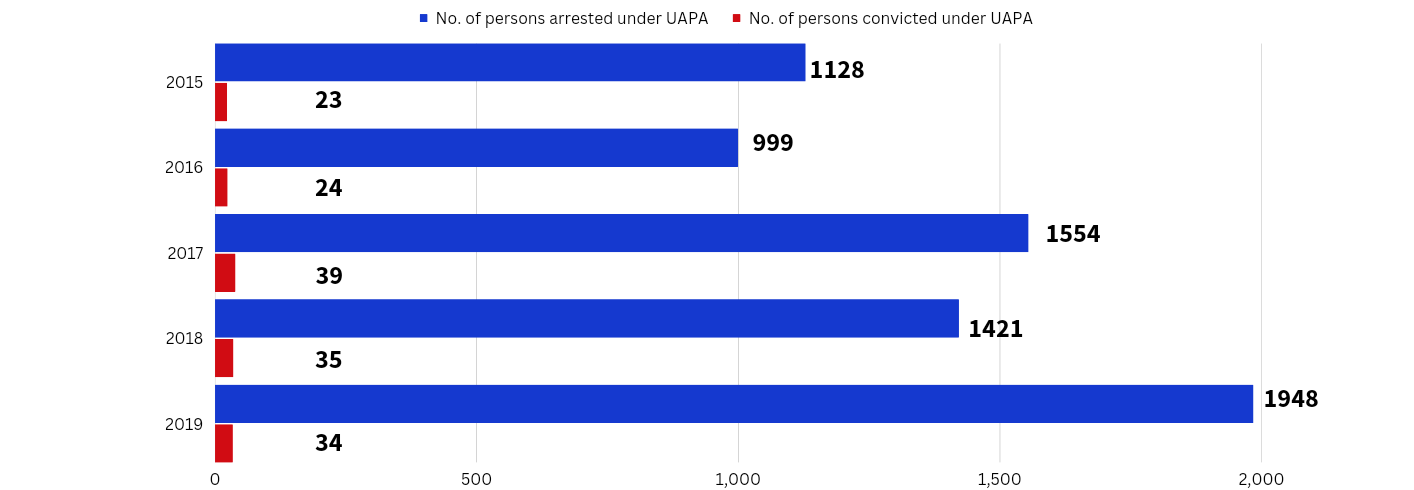

On top of the elongated pre-charge detention period authorized by the contentious Act, the delay caused by the authorities, in framing the chargesheet, plays a significant role in slowing down the process of imparting justice to the accused. The Ministry of Home Affairs, while replying to one of the questions of the Rajya Sabha, stated the following details [21]:

The given table suggests that most of the registered cases took more than 180 days to frame the chargesheet and some are yet to be framed. In the year 2021, 43 cases were registered by the NIA under sedition or UAPA till the date of 13 December 2021 out of which 28 cases are those in which the chargesheet has not yet been filed [22].

Hence, more than half of the cases registered still remain under the pre-chargesheet detention phase. There is no data found that shows that in cases relating to delayed charge sheet framing, whether the accused were granted bail or not.

The accused not only suffers from the tedious stretch of criminal proceedings against him, but he also has to go through with the extended and prolonged dawdling of the pre-charge detention period. Such circumstances become even more perturbing when 53% of the persons arrested under the UAPA in 2018, 2019, and 2020 are under the age of 30 years [23].

In the case of Mohammad Ilyas and Mohammad Irfan, who were in their 30s when arrested, accused of being associated with Lashkar-e-Taiba (notified as an illegal organization and banned in India) were arrested under the provisions of the UAPA in August 2012. After 9 long years in custody, the court cleared them of all the charges due to lack of evidence in June 2021 [24].

Additionally, the Act provides for rigid bail and bond provisions. Bail can only be granted to the accused if it is sought to be agreed upon by the Public Prosecutor. Such a provision curtails the right of the accused to be released on bail provided by the due process of law.

In the case of non-Indians, the right to be released on bail is altogether unavailable and no bail can be granted to such a person. Such provisions are a total violation of the principle-“Bail is Right and Jail is Exception”. Besides this, the accused is also denied anticipatory bail in all respects as per the provisions of the Act [25].

In the case of Stan Swamy v. The State of Maharashtra, an 84-year-old priest was arrested on 8 October 2020 by the NIA under the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act and was charged for his alleged involvement in Bhima Koregaon Violence (2018), and that he was connected to the Communist Party of India.

The NIA court rejected the temporary bail application filed on medical grounds. Further, Swamy was denied his straw and sipper which he needed to drink water since he was not able to carry a glass due to Parkinson’s.

A second bail application was filed however, the jury postponed the hearing and ordered the Taloja Jail authorities to provide him with straw and sipper and warm clothes. Swamy was denied another bail on the ground that “collective interest outweighs the right to personal liberty”. After repeated bail applications on the grounds of his poor health and age, Swamy was still not granted bail.

He was admitted to a private hospital as per the directions of HC and died on 03 July 2021, a day prior to his bail hearing in the court.

Lawyers defending Swamy accused the jail authorities of their negligent conduct and NIA of not granting bail [26].

Such rigid provisions of the Act cause unnecessary harassment and trouble to innocent citizens. This way the Act loses its actual object and becomes a medium for the insensitive and inhumane treatment towards innocents.

Conclusion

Although the intent behind the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act was never to create disruption in society, excessive and arbitrary powers awarded to the Executive has led to misuse of the Act. The adverse effects of giving the authorities such excessive powers are that they are misinterpreting and negligently invoking the provisions of the Act.

The Act is now a weapon against protests and Freedom of Speech and Expression under the Fundamental Rights of the Constitution. It acts as a tool to subdue any political oppression. Mere invocation of the Act against the accused has resulted in years of custody and in some cases death.

Such grave allegations without any legitimate proof are seriously a concerning issue for society in general. The Amendments made in 2019 are controversial in nature and have led to innocent citizens facing a huge deal of trouble. Though a specific mention of ‘national security’ is made under the DPSP, the fundamental rights of liberty, speech and association precede application. Fundamental Rights cannot be compromised for illegitimate purposes.

Though in recent times, the judiciary has become far more transparent and empathetic in relation to cases under UAPA; many cases are left for the NIA Courts to deal with. It is still a long way for it to take steps in repealing certain provisions of the Act which are considered a threat to an individual’s fundamental rights. Until then, clear and liberal interpretations of the provisions are necessary for harmonious working.

By Dhanvi Joshi, 5th Year B.A. LL.B. (Hons.), Faculty of Law, The Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda, Vadodara