Introduction

Before going into detail, let us first discuss the meaning of ‘state of emergency’ (hereinafter ‘emergency’) in general. In layman’s language, emergency means a situation wherein there is a failure in the system of the government to such an extent that it calls for urgent action so that adequate measures can be undertaken to rebut a situation.

Across the globe, generally during an emergency, the Centre takes control over all the functions and decision-making powers, irrespective of the fact that whether the nation is federal or unitary, bicameral or unicameral, democratic or autocratic.

This power of the Centre is generally conferred upon the President of the nation concerned, and he/she is permitted to perform such powers during a state of disaster, civil unrest, or armed conflict. The concept of emergency is found in the Roman Law, wherein Justitium (state of emergency) could be proclaimed by the Senate by putting forward a final decree (senatus consultum ultimum), and this final decree was of such a nature that it was not subject to any dispute.

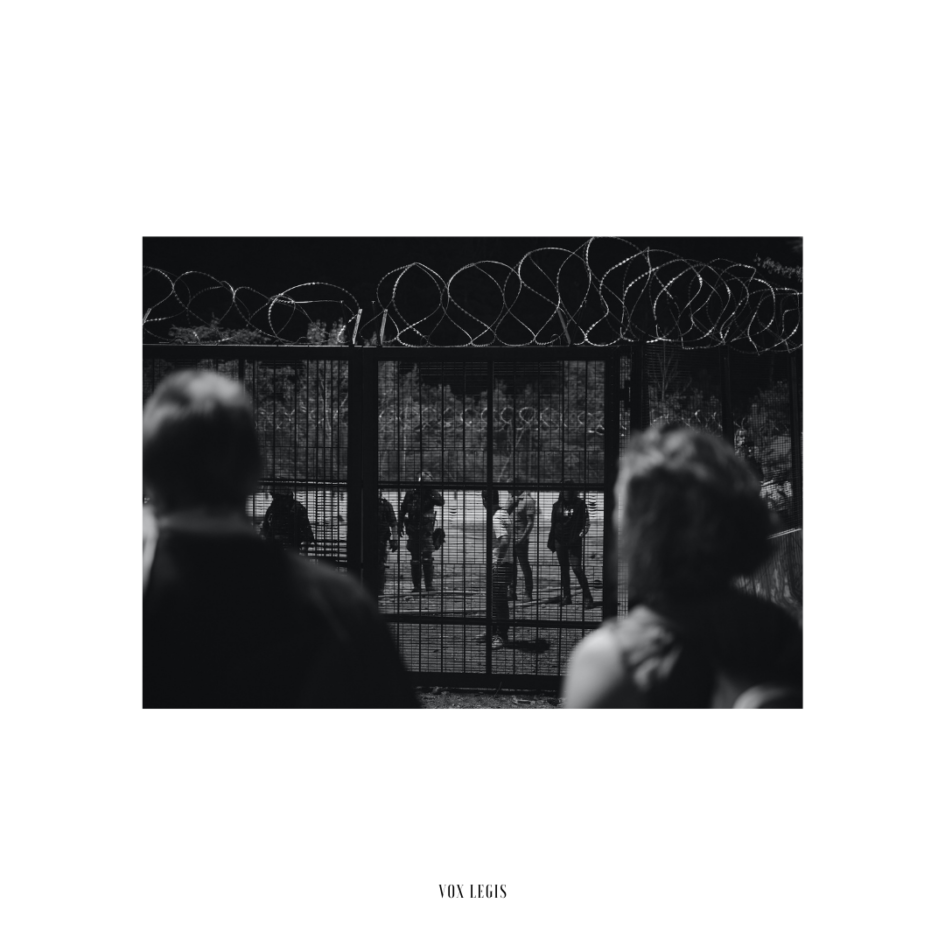

State of emergency can also be used as a rationale or pretext for suspending rights and freedoms guaranteed under a country’s constitution or basic law. The procedure for and legality of doing so vary from country to country.

This article shall only be confined to ‘National Emergency Provisions’. In this article, the author shall primarily focus on the evaluation of national emergency provisions in India and Germany over the years; the provisions (procedure) which give effect to the state of national emergency in various countries (India and Germany), and thus, render a comparative analysis thereof.

Moreover, the article shall also postulate the national emergency provisions of these countries with various international conventions and covenants. And, at the end of the article, apart from conclusion, the author shall outline a comparative analysis pertaining to the national emergency provisions between the two nations in the form of a brief observation, so as to construe the present articulation in a more harmonious and simplified manner.

EVOLUTION OF NATIONAL EMERGENCY PROVISIONS

INDIA:

It is a well-known fact that the framers of the Indian Constitution adopted the national emergency provisions from the German Constitution. However, the question which arises is what was the scenario before the year 1950? Were there no national emergency provisions?

As far as pre-1950 is concerned, the Government of India Act, 1935 (hereinafter the ‘1935 Act’) did contained the provisions pertaining to national emergency. Section 12(1) of the 1935 Act defines some special responsibilities of the Governor General, including ‘(a) the prevention of any great menace to peace or tranquility of India; and (b) safeguarding of the financial stability and credit of the Federal government’.

On the top of that, the 1935 Act also enunciated certain limitations of the constitutional emergency powers. It stated that such emergency provisions shall be invoked only as (a) last resort; (b) shall be time bound; and (c) shall be for the preservation and re-establishment of the constitutional norm.

Moreover, the 1935 Act provided for two types of emergencies: S.45, relating to those emerging from a failure of constitutional machinery; and S.102, relating to those arising due to ‘war or internal disturbance’. This power to proclaim national emergency was vested in the Governor General.

The proclamation under the 1935 Act had a time period of ‘six months’ from the date of proclamation, and could further be extended only after procuring approval from the British Parliament.

GERMANY:

In Germany, before the Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany came in to effect in 1949 (i.e. German Constitution), the Weimar Constitution (1919-1933) was in force. Article 48 of the Weimar Constitution dealt with the aspect of national emergency provisions. As per Article 48, the President had the power to proclaim emergency under certain circumstances.

But, before the proclamation of emergency, a ‘decree’ had to be issued by the President from the Reichstag (Lower House). The Reichsrat (Upper House) was not involved in the above process at all. The Reichstag (Lower House) had the power to revoke or nullify the proclamation by way of ‘simple majority’.

However, it is to be noted that this power of the Reichstag (Lower House) could be curtailed by way of Article 25 of the Weimar Constitution, which stated that the President could retaliate against the Reichstag (Lower House) by using the power to dissolve the latter and call for new elections within 60 days.

This gave the President unlimited vis-à-vis discretionary powers during proclamation of national emergency, as, neither the judiciary nor the legislature had any sort of control or check over the executive’s functions.

Thus, even though on one hand the Reichstag (Lower House) had the power to nullify the proclamation, they never utilized such power, out of the fear of dissolution. Moreover, under Article 48, the government was given authority to curtail constitutional rights including habeas corpus, free expression of opinion, freedom of the press, rights of assembly, and the privacy of postal, telegraphic and telephonic communications.

Finally, in the year 1949, this draconian article in particular and the Weimar Constitution in general was repealed and replaced by the Basic Law Constitution (Grundgesetz).

NATIONAL EMERGENCY PROVISIONS IN THE PRESENT CONSTITUTION: PROCEDURE AND EFFECT ON VARIOUS RIGHTS

INDIA:

A. PROCEDURE:

In India, the emergency provisions are enshrined under Part XVIII (Articles 352 to 360) of the Constitution of India, 1950 (hereinafter ‘the Indian Constitution), which is pertaining to ‘Emergency Provisions’. The important provisions relating to National Emergency are Articles 352, 353, 358 and 359. In a jest, Article 352 of the Indian Constitution enunciates that if the President of India is satisfied that there is grave and imminent danger to the security of India or any part of its territory, which is either threatened by war or external aggression or armed rebellion, then, in such a case, he may, by proclamation issue national emergency throughout the nation or any part thereof. It is to be noted that earlier the words were ‘internal disturbance’ which were later substituted by ‘armed rebellion’ by way of 44th Amendment of 1978 due to vagueness of the terminology and its misuse thereof. However, such proclamation can be issued by the President only after the Union Cabinet (consisting of the Prime Minister and Council of Ministers) communicates a grant in writing to him.

Moreover, every proclamation shall also be laid before each House of Parliament. The time period of national emergency is one month from the date of proclamation. The same can be extended if the House of Parliament approves it before the expiration of the emergency period. It is noteworthy that, if it is a Proclamation revoking the previous Proclamation, it is then not necessary to lay down the same in the House of Parliament. Furthermore, if the House of People has been dissolved before or during the time of emergency, then, in such a case, the proclamation shall cease to operate after expiry of one month. However, if during such period, a Resolution approving the proclamation has been passed by the Council of States, then the proclamation shall continue to operate for such further period until the House of People is reconstituted. The proclamation shall cease to operate within ‘thirty days’ from the day House of People has been reconstituted. But, after such reconstitution, if the House of People approves extension of the emergency, then, the emergency shall remain in force for a further period of ‘six months’.

It is also to be observed that a “resolution may be passed by either House of Parliament only by a majority of the total membership of that House and by a majority of not less than two-thirds of the Members of that House present and voting.” Moreover, it is noteworthy that the President can issue proclamation of national emergency not only in the plight of actual and real danger, but, may also issue the same on the ground of ‘imminent danger’.

Article 353 is pertaining to “Effect of Proclamation of Emergency”. Under this, one intriguing clause is ‘clause (b) of Article 353’, which states that the Parliament has the power to make such laws and confer powers and duties to the Union which is not enumerated in the Union List. Thus, during national emergency, the Union can have the powers enunciated in the State List also, if the Parliament makes law/s regarding the same.

B. EFFECT ON VARIOUS RIGHTS:

There are certain unusual effects on various rights when the national emergency is in existence. These effects have been enshrined under Articles 358 and 359 of the Indian Constitution. Article 358 is relating to “Suspension of provisions of article 19 during emergencies.”

According to this article, during the proclamation of national emergency, all the provisions of Article 19 shall be suspended (such as freedom of speech and expression, right to assemble peaceably and without arms), and the State shall have the power to make any law or to take any executive action thereof.

Another provision is Article 359 which is pertaining to “Suspension of the enforcement of the rights conferred by Part III during emergencies”, and states that when the proclamation of emergency is in operation, the ‘President’ may by order declare that the right to move any Court for the enforcement of any right conferred under Part III shall remain suspended until the proclamation is in force.

However, it is noteworthy to appreciate the efforts of the Parliament to alter the said provision in 1978, by way of 44th Amendment Act of 1978. Now, even during proclamation of emergency, Articles 20 (Protection in respect of conviction for offences) and 21(Protection of life and personal liberty) shall remain operative, and for violation of any right under the said articles, an individual shall have the right to move to any Court for its enforcement.

GERMANY:

A. PROCEDURE:

During the Second World War, Hitler had invoked the emergency provision under Article 48 of the Weimar Constitution for a record ‘250 times’. Because of such misuse, not only Article 48, but the Weimar Constitution altogether was struck down after the end of the war.

A new constitution was formed by the Allied Control Council (consisting of the U.K., the U.S.A., France and the Soviet Union), namely, Basic Law for Federal Republic of Germany, 1949 (German word – Grundgesetz). However, due to disastrous consequences in the past, the framers of the Basic Law Constitution did not find it suitable to insert any sort of emergency provisions in the new constitution.

It was in 1968, almost two decades after the new constitution came in to force and after ten years of discussion, that finally an amendment to the Basic Law Constitution was made by way of 17th Constitutional Amendment to the Basic Law Constitution.

On May 30, 1968, the Germany Emergency Acts, 1968 (hereinafter ‘the 1968 Act’) was passed, which contained provisions regarding proclamation of state of emergency. However, this time around, utmost caution was taken while drafting the emergency provisions.

For instance, the President’s power with respect to proclamation was not absolute unlike Article 48 of the Weimar Constitution. Under the 1968 Act, the Judiciary and the Legislature (both houses) were given the power to monitor and have a check on the Executive’s action during state of emergency.

If during emergency, the House of Parliament is unable to convene sessions, then, a ‘Joint Committee’ shall be formed consisting two third members of Bundestag (Lower House) and one third members of Bundesrat (Upper House), which shall continue its routine functions, except amending the Basic Law Constitution. This was not provided in the Weimar Constitution of 1919.

B. EFFECT ON VARIOUS RIGHTS:

As far as the effect of proclamation of emergency is concerned, the Basic Law Constitution (Grundgesetz) provides certain powers to the President. For instance, Article 10 of the constitution talks about ‘Limitation of Basic Constitutional Rights’.

According to Article 10 of the Grundgesetz, limitations may be placed on privacy of correspondence, confidentiality of telecommunication and of postal communication, in order to protect the free and democratic constitutional order. Freedom of movement may also be limited under certain conditions.

Occupational freedom (the right to pursue a career of one’s choice) may also be altered. However, this time, to appease the critics of emergency provisions, a fourth paragraph was introduced in Article 20 (Right to Resist), which stated that the people of Germany has the right, if no other remedy was possible, to resist anyone trying to go against the constitutional laws.

Nowhere, the duration of emergency has been mentioned. Thus, it can be concluded that emergency under the Basic Law can go on for perpetuity.

NATIONAL EMERGENCY PROVISIONS VIS-À-VIS INTERNATIONAL LAWS

Under international law, rights and freedoms may be suspended during a state of emergency; for example, a government can detain persons and hold them without trial. All rights that can be derogated from, are listed in the International Covenant for Civil and Political Rights (hereinafter ‘ICCPR’).

Non-derogatory rights cannot be suspended. Non-derogatory rights are listed in Article 4 of the ICCPR; they include right to life, the rights to freedom from arbitrary deprivation of liberty, slavery, torture, and ill-treatment.

Some countries have made it illegal to modify emergency law or the constitution during the emergency; other countries have the freedom to change any legislation or rights based constitutional frameworks at any time that the legislative chooses to do so.

Constitutions are contracts between the government and the private individuals of the particular country concerned. The International Covenant for Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) is an international law document signed and ratified by states.

Therefore, the Covenant applies to only those persons acting in an official capacity, not private individuals. However, States Parties to the Covenant are expected to integrate it into national legislation.

From the above, it first of important to verify whether India and Germany are States Parties to the ICCPR?

If yes, then, the second question which arises is whether all or any of them have complied with the ICCPR with respect to the emergency provisions?

India and Germany, both are parties to the ICCPR. Both have signed, ratified/acceded and entered the covenant in to force. As far as complying with the framework of the ICCPR pertaining to the emergency provisions is concerned, both the nations abovementioned do comply.

For instance, the ICCPR states that rights under Article 4 (such as right to life) are non-derogatory in nature, and thus, cannot be suspended even during proclamation of emergency. India too under Article 359 of the Indian Constitution clearly specifies that all the provisions under Part III shall remain suspended during emergency ‘except Articles 20 and 21’, which deals with preventive detention and right to life and personal liberty respectively.

OBSERVATIONS AND CONCLUSION

In conclusion, the author while articulating this article made certain observations which are as follows:

a. It is no doubt that India adopted the emergency provisions from Germany. However, what is generally misconstrued is that the former adopted the emergency provisions of the latter in absolute terms. It rather seems to be in “relative terms”. For instance, at first, the President of India can proclaim emergency only for a duration of one month, and thereafter, it might be extended. Whereas, in case of Germany, no duration has been specified.

b. During Emergency, German Constitution provides for the ‘Right to Resist’ under paragraph 4 of Article 20, which gives a right to the people of Germany to resist anyone trying to go against the constitutional laws. The same right is not explicitly present in the Indian Constitution. However, by virtue of the 44th Amendment to the Indian Constitution [1978], to some extent such right to resist has been conferred to the people of India also. Having a perusal of Article 359 of the Indian Constitution (relating to ‘Suspension of the enforcement of the rights conferred by Part III during emergencies’), it can be observed that even though all the other fundamental rights are been suspended/derogated during emergencies, rights enshrined under Articles 20 and 21 shall still remain enforceable.

c. Lastly, as per the Indian Constitution, when emergency is proclaimed, if the both the House of Parliament are dissolved, they are not required to be in session. However, as per the German Constitution, if the House of Parliament (Bundestag and Bundesrat) are not in session during emergency, then, a Joint Committee shall be constituted which shall monitor the actions of the Executive. In the opinion of the author, India being not one-of-the, but ‘the’ largest democracy around the globe, at some point of time shall adopt and insert such a provision in to the Indian Constitution, so that the power to proclaim emergency cannot be misused or abused even in the slightest of the way[s].

Hence, from the above, it is depicted that even though both the nations [India and Germany] have different procedures relating to the proclamation of national emergency, still they have one thing in common; and that is, both of them have provisions which upholds the human rights of the people of the respective nations even during a state of national emergency.

By Adv. Shaunak Rajiv Shah, an alumnus of Faculty of Law, The Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda, Vadodara (Batch 2016-2019).